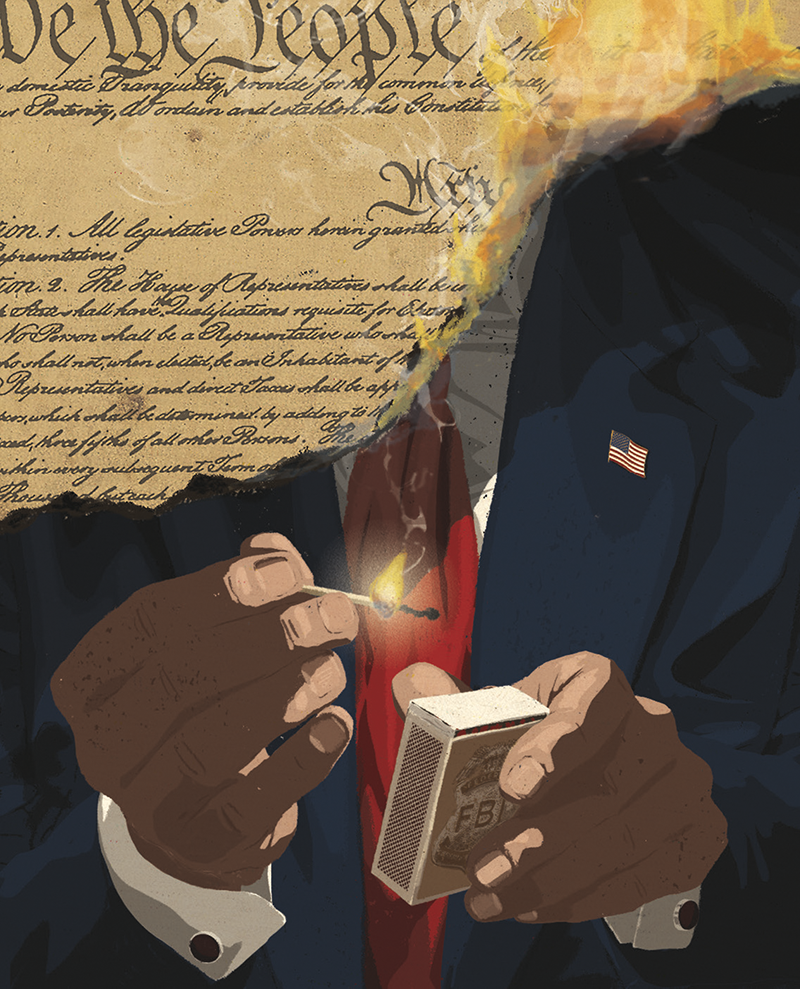

A few hours before the inauguration ceremony, the prospective president receives an elaborate and highly classified briefing on the means and procedures for blowing up the world with a nuclear attack, a rite of passage that a former official described as “a sobering moment.” Secret though it may be, we are at least aware that this introduction to apocalypse takes place. At some point in the first term, however, experts surmise that an even more secret briefing occurs, one that has never been publicly acknowledged. In it, the new president learns how to blow up the Constitution.

The session introduces “presidential emergency action documents,” or PEADs, orders that authorize a broad range of mortal assaults on our civil liberties. In the words of a rare declassified official description, the documents outline how to “implement extraordinary presidential authority in response to extraordinary situations”—by imposing martial law, suspending habeas corpus, seizing control of the internet, imposing censorship, and incarcerating so-called subversives, among other repressive measures. “We know about the nuclear briefcase that carries the launch codes,” Joel McCleary, a White House official in the Carter Administration, told me. “But over at the Office of Legal Counsel at the Justice Department there’s a list of all the so-called enemies of the state who would be rounded up in an emergency. I’ve heard it called the ‘enemies briefcase.’ ”

These chilling directives have been silently proliferating since the dawn of the Cold War as an integral part of the hugely elaborate and expensive Continuity of Government (COG) program, a mechanism to preserve state authority (complete with well-provisioned underground bunkers for leaders) in the event of a nuclear holocaust. Compiled without any authorization from Congress, the emergency provisions long escaped public discussion—that is, until Donald Trump started to brag about them. “I have the right to do a lot of things that people don’t even know about,” he boasted in March, ominously echoing his interpretation of Article II of the Constitution, which, he has claimed, gives him “the right to do whatever I want as president.” He has also declared his “absolute right” to build a border wall, whatever Congress thinks, and even floated the possibility of delaying the election “until people can properly, securely, and safely vote.”

“This really is one of the best-kept secrets in Washington,” Elizabeth Goitein, the co-director of the Liberty and National Security Program at NYU’s Brennan Center for Justice, told me. “But though the PEADs are secret from the American public, they’re not secret from the White House and from the executive branch. And the fact that none of them has ever been leaked is really quite extraordinary.” Goitein and her colleagues have been working diligently for years to elicit the truth about the president’s hidden legal armory, tracing stray references in declassified documents and obscure appropriations requests from previous administrations. “At least in the past,” said Goitein, “there were documents that purported to authorize actions that are unconstitutional, that are not justified by any existing law, and that’s why we need to be worried about them.”

Part of what makes the existence of PEADs so alarming is the fact that the president already has a different arsenal of emergency powers at his disposal. Unlike PEADs, which are not themselves laws, these powers have been obligingly granted (and often subsequently forgotten) by Congress. They come into force once a president declares a state of emergency related to whatever crisis is at hand, though the link is often tenuous indeed. For example, to fight the war in Vietnam, Lyndon Johnson used emergency powers originally granted to Harry Truman for the Korean War. As Goitein has written, the moment a president declares a “national emergency”—which he can do whenever he likes—more than one hundred special provisions become available, including freezing Americans’ bank accounts or deploying troops domestically. One provision even permits a president to suspend the ban on testing chemical and biological weapons on human subjects.

Thinly justified by public laws, these emergency powers have become formidable instruments of repression for any president unscrupulous enough to use them. Franklin Roosevelt, for example, invoked emergency powers when he incarcerated 120,000 Americans of Japanese ethnicity. One of them, Fred Korematsu, a twenty-three-year-old welder from Oakland, California, refused to cooperate and sued. His case reached the Supreme Court, which duly ruled that the roundup of U.S. citizens had been justified by “military necessity.” Justice Robert Jackson, one of three dissenters, wrote that though the emergency used to justify the action would end, the principle of arbitrary power sanctified by the court decision “would endure into the future, a loaded weapon ready for the hand of any authority that can bring forward a plausible claim of an urgent need.”

Jackson’s warning now rings louder than ever, given the spectacle of a president who revels in displays of arbitrary power. His boasts are clearly not idle, and have duly elicited a chorus of alarmed protest, amplified by the prospect of an election that could certify his grip on power for (at least) another four years. In the event of his displacement, sooner or later, by a more conventional chief executive pledged to respect our laws and institutions, we might hope that Congress would move aggressively to assert the Constitution and close all the secret loopholes Trump so cherishes. After all, this has happened before. Half a century ago, a president was caught acting lawlessly, sparking national outrage and prompting a reckoning with how extensively arbitrary presidential power had eaten away at Americans’ freedoms. Back then, Congress seemed resolved to prevent such abuses from happening again. But the attempt was brief; the impulse rapidly faded. Given the threats facing what is left of our liberty today, it is important to look at what happened, and why.

In the 1970s, the Colorado senator Gary Hart served on the famed Church Committee, which probed and exposed CIA assassinations, FBI operations to subvert and destroy the civil-rights movement (including efforts to drive Martin Luther King Jr. to suicide), and other secret, scandalous initiatives. These shocking revelations, including close ties to organized crime, revealed the terrifying extent of unbridled presidential power, with the use of secret police—the FBI and CIA—as personal instruments. Given Hart’s time on the committee, one would expect him to be intimately familiar with the secret powers of the president. Yet when he read an April 10 op-ed in the New York Times by Goitein and her colleague Andrew Boyle headlined trump has emergency powers we aren’t allowed to know about, he was caught by surprise. “It snapped my head back,” he told me.

Even though Hart, now retired and living in the Rocky Mountains, was deeply immersed in matters of national security and intelligence for decades, he had not heard about the extraordinary powers that Goitein and Boyle were describing. Throughout his work on the Church Committee, he said, “We did not come across, did not examine, the so-called secret powers put in place in anticipation of a nuclear attack.” He was shocked to learn not only that they existed, but that they had expanded in recent years. “One would have thought that, with the end of the Cold War in the early Nineties, the secret powers would have been put on the shelf somewhere,” he said. After reading the op-ed, Hart called several “close friends” who had formerly occupied “very, very senior” defense and security posts. Some responded with claims of ignorance. Others refused to talk at all. “People I know well, who had to know about these powers, simply refused to even send an email back saying ‘I can’t talk about it,’ ” said Hart. “They just clammed up.”

When Hart assumed office in 1975, Washington was still reverberating from the twin earthquakes of Watergate and the Vietnam War. Americans had learned that a president could use his power in ways both shocking and criminal. Richard Nixon had flouted the law with an easy conscience, commissioning burglaries and directing a cover-up. His defense, as he later described it, was that “when the president does it, that means that it is not illegal.” The Vietnam disaster had spurred Congress to pass the War Powers Act a year and a half earlier, overriding a presidential veto with a two-thirds majority in both houses. Authored by the liberal Republican congressman Paul Findley, the act barred the president from going to war without authorization from Congress (or so its sponsors believed). Now, as Hart’s tenure began, the Capitol was being further rocked by revelations of a vast and illegal domestic spying operation and the first hints of an assassination program. In response, Congress created two committees to investigate the CIA—one headed by the young and ambitious senator Frank Church of Idaho, the other eventually led by Representative Otis Pike, a tough ex-Marine from New York.

Over the next year, the committees found copious evidence that presidents and their agents had routinely strayed outside the Constitution. As the Senate committee’s chief counsel, F.A.O. “Fritz” Schwarz Jr., told me, he and his colleagues initially assumed that they would simply be investigating Nixon’s wrongdoings and CIA “improprieties.” But it soon became clear that the rot went far deeper. “It wasn’t only a Nixon problem,” he said. “It was not only a CIA problem. The abuses of power go back to at least Franklin Roosevelt.” Roosevelt, they found, had commissioned FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover to uncover evidence of “subversion” (without defining what that meant) in the lead-up to World War II, requesting that such investigations be limited “insofar as possible” to “aliens.” Along with Hoover and U.S. attorney general Homer Cummings, FDR agreed that the investigations should be kept secret from Congress.

As he learned how the FBI had also attempted to destroy the civil-rights movement, Schwarz came to believe that, compared with the CIA, “the FBI was the greater danger to American democracy,” especially when deployed in the political service of a chief executive. Johnson, for example, had directed a “special squad” in the FBI to spy and report on opposition groups during the 1964 Democratic National Convention. “It’s a tendency among presidents to say, ‘Gosh, we have these resources, let’s use them,’ ” said Schwarz. “If you have power, you can get more.”

While the two intelligence committees generated exciting headlines (though Pike’s discovery that the most frequent CIA covert action was to interfere in other countries’ democratic elections passed almost entirely without comment), a third committee was probing equally momentous issues in quiet obscurity. In 1972, a number of senatorial elders, including the Republican Charles Mathias of Maryland, having noted the use of antediluvian emergency powers to prosecute the disastrous Vietnam War, had instituted the Special Committee on the Termination of the National Emergency. Co-chaired by Church and Mathias, its task was to unearth and revoke those emergency powers that were authorized by Congress and subsequently forgotten.

The first problem faced by the committee was to find out what emergency powers existed. “This,” read a 1973 report, “has been a most difficult task.” Nowhere in government was there a complete catalogue detailing these emergency laws, which were buried within the vast body of laws passed since the first Congress. “Many were aware that there had been a delegation of an enormous amount of power, but of how much power no one knew,” the committee said. Then, just when the staff had resigned themselves to poring over all eighty-seven volumes of the Statutes at Large—the record of all laws and resolutions passed by Congress—they discovered a shortcut. As part of their COG arrangements, “The Air Force had digitized the whole thing,” Patrick Shea, a Church aide who worked as a staffer on the committee, told me recently. “They had it on computer tape, buried inside a mountain—NORAD headquarters—outside Colorado Springs, in case there was a nuclear war.”

Using the digitized records, aides searched for keywords that might have been used when describing “extraordinary powers”: “war,” “national defense,” “invasion,” and “insurrection.” The opening paragraph of the committee’s initial report made their findings clear:

A majority of Americans alive today have lived all of their lives under emergency rule. For forty years, freedoms and governmental procedures guaranteed by the Constitution have, in varying degrees, been abridged by laws brought into force by states of national emergency.

In addition to Johnson’s use of Truman’s Korean War powers, the committee noted that FDR had relied on an old wartime measure, introduced by Woodrow Wilson in 1917, to close the banks in 1933 in response to the Great Depression. To his amusement, Shea even discovered that a Civil War–era emergency law enabling cavalry on the Western plains to buy forage for their horses had been used to skirt Congress in financing the war in Vietnam.

Before the committee’s investigation, no one had realized that “temporary” states of emergency could become permanent. “Because Congress and the public are unaware of the extent of emergency powers,” it found, “there has never been any notable congressional or public objection made to this state of affairs. Nor have the courts imposed significant limitations.” The drafters of these emergency powers, whoever they were, “were understandably not concerned about providing for congressional review, oversight, or termination of these delegated powers.” By way of comparison, the report cited a 1952 opinion by Justice Jackson, in which he described the emergency powers granted by the constitution of the Weimar Republic. Instituted following World War I, it was expressly designed to secure citizens’ liberties “in the Western tradition.” However, it also empowered the president to unilaterally suspend any and all individual rights in the interest of public safety. After various governments had made temporary use of this provision, read Jackson’s account, “Hitler persuaded President Von Hindenburg to suspend all such rights, and they were never restored.”

The committee concluded that a president could “seize property and commodities, seize control of transport and communications, organize and control the means of production, assign military forces abroad, and restrict travel”—a state of affairs that the committee reasonably described as “dangerous.” As ominous as the committee’s discoveries may have been, however, they received scant media attention, lacking the sex appeal of assassination plots, poison dart guns, or White House liaisons with the Mafia. When I asked Shea why else these revelations might have attracted such little notice, he told me that Church “wasn’t so anxious for publicity” in 1973, when the emergency committee was first set up. It was only after Church had been given control of the intelligence committee and had decided to run for the 1976 Democratic nomination, said Shea, that he wanted “all the publicity he could get.” (To secure the assignment, Church had falsely promised the Senate leadership that he would not run.) As for Mathias, who had helped sound the alarm about emergency powers in the first place, Shea told me that he “always liked to stay in the background. He was the soul of discretion. There were people like that in the Senate in those days.”

By 1974, the emergencies committee had drafted a bill that ended most existing emergencies and mandated the automatic termination of new ones after six months. Yet the bill’s passage was continually delayed, and its contents were steadily watered down, thanks in large part to what Jerry Brady, a former chief of staff on the committee, recalled as “pretty vigorous pushback from the president and others at the White House.”

We now know, thanks to declassified archives, that the administration kept tight supervision over the committees’ work, and that Henry Kissinger urged unyielding resistance. As he exclaimed during a meeting with President Gerald Ford and others in May 1975: “It is an act of insanity and national humiliation to have a law prohibiting the president from ordering an assassination.” The White House deputy chief of staff, Dick Cheney, whose most distinguishing feature, according to another senior Ford aide, were his “snake-cold eyes, like a Cheyenne gambler’s,” also attempted to thwart the investigations behind the scenes. After reviewing thousands of declassified documents, the National Security Archive reported in 2015 that Cheney ultimately decided which documents requested by Church and his staff should be handed over, and that “CIA accommodation measures were explicitly designed to keep Church Committee investigators away from its most important records.” (Among those assigned to this task in the CIA legislative office was a conservative young lawyer named William Barr.)

Little wonder, then, that the effort “to terminate the national emergency” failed. The bill did manage to abolish existing states of emergency. (This provision was supposed to kick in after six months, though it was pushed back to two years.) But automatic suspension of new emergencies, as originally proposed, gave way to a requirement that Congress should meet twice a year “to consider a vote” on termination. Its force thus quietly diluted, the bill finally became law in 1976, whereupon Congress swiftly forgot about it, never once meeting to vote on whether to end states of emergency. The provision allowing Congress to end them through a “concurrent resolution” that did not require a president’s signature was obviated by a Supreme Court decision in 1983, and any such resolution has required a veto-proof majority ever since.

So total was Congress’s failure to follow through on limiting emergency powers that in 1977 it actually voted to expand them. That year, it passed the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, which enables the president to declare national emergencies “to deal with any unusual and extraordinary threat” that “has its source in whole or substantial part outside the United States.” The law empowers presidents to sanction countries, businesses, and individuals without warning, without furnishing evidence, and, effectively, without appeal. As I have previously reported in Harper’s Magazine, the Office of Foreign Assets Control, which operates under the 1977 law, can freeze an American’s bank account while offering nothing more than a vague explanation.

The intelligence committees, whose revelations had been far more dramatic than those of the emergencies committee, had no more success in curbing executive authority. Congress avoided pinning responsibility on presidents for ordering assassinations—Church apparently feared that antagonizing the Kennedy family by publicizing JFK’s role in such plots would imperil his presidential hopes. (The Pike Committee staff took a more hard-nosed view: “We laughed when Church described the CIA as a ‘rogue elephant,’ ” one former staffer, Greg Rushford, told me. “We knew they were the president’s guys.”) The net result of the inquiries was the creation of permanent secret committees in the House and Senate to provide “oversight” of the intelligence agencies. “If they were going to do something that had potential blowback, they had to let us know ahead of time,” Hart, who was a member of the new Senate oversight committee, told me. “I don’t recall in my original years there that we ever vetoed an operation. But they did notify us of things they were going to do.”

The new House committee appeared no more inclined to make waves. “We’re the oversight committee—we commit oversights,” joked Richard Anderson, a CIA analyst who joined the committee in 1978. As with the international economic powers legislation, Congress dutifully provided a measure, the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), that purported to rein in the executive’s power to spy on citizens while merely legalizing it. Passed with a large bipartisan majority, the law set up a court composed of eleven judges to secretly grant “warrants” for wiretaps and burglaries. The ACLU’s chief legislative counsel Jerry Berman protested that the proposed law “broadly authorizes intrusive investigations of American citizens. It takes away the inherent power of the president to do these things, but then gives him the express power to do them, with all the flexibility that he had before.” A simple statistic from the FISA court suggests that Berman’s concerns were well-founded: of 33,900 applications for FISA warrants between 1979 and 2012, precisely eleven were rejected.

The ensuing decades demonstrated in grim relief just how limited the successes of the 1970s had been. Ronald Reagan presided over a wide-ranging covert operation in Nicaragua using money generated by secret arms sales to Iran and simultaneously conducted an illegal domestic propaganda campaign to generate support. When the Iran-Contra scandal was exposed, Congress professed outrage and went through the motions of an investigation that not only shrank from targeting Reagan himself or revealing the sum total of his minions’ misdeeds (including rehearsals for mass roundups of “subversives”), but ensured that the principal perpetrators escaped punishment entirely. George H. W. Bush attacked Panama without congressional approval (but fortified by a legal opinion from Assistant Attorney General William Barr) only a few years later, while Clinton would do the same in Serbia. George W. Bush used congressional authorization for military force against Al Qaeda after 9/11 to occupy Iraq, illegally wiretapping Americans all the while. Barack Obama broke new extra-constitutional ground in ordering the execution by drone of a U.S. citizen. None suffered more than brief censure, and all are now remembered with respect, even reverence.

Donald Trump can expect no such indulgence, nor does he seem to want it. As the seventeenth-century French moralist Francois de La Rochefoucauld wrote, “Hypocrisy is the tribute vice pays to virtue.” Trump, never troubling to disguise his disregard for the law, is clearly no hypocrite. His evident lack of scruples—along with the primal terror induced by the prospect of a second term—is the very reason that the long-dormant issue of emergency presidential powers has now come to the fore.

In June, McCleary and Mark Medish, a senior National Security Council director under Clinton, joined Hart and former senator Tim Wirth to warn in Politico that in the event of “a national emergency on the grounds of national security, the president would have more than 120 statutory emergency powers” at his disposal, potentially enabling him to postpone the election. “It looks as though a rolling coup is underway, with Trump and his confederates testing the waters for ways to scupper the election,” Medish told me recently. Democratic leaders are meanwhile cautious, he said, “about doing anything that might demoralize voters by drawing too much attention to unconventional election threats,” which they feel would risk depressing the vote.

As McCleary pithily remarked, when the president decides to ignore it, the Constitution turns out to be “no more than a gentleman’s agreement.” But there is little sign that Congress is prepared to treat executive power—both secret and otherwise—as a fundamental problem that will endure when or if Trump retreats to Mar-a-Lago. Admittedly, the Democrats sought to bring down Trump over his maladroit dealings with Ukraine, but the initiative died a predictable death. The days of bipartisan revolt against unchecked presidential power are long gone.

“It was a time that is unlikely to be duplicated anytime soon,” Jack Boos, who served as counsel for the Pike Committee, told me sadly. “We had a major scandal and a weakened presidency. It was a perfect storm that many thought could be exploited and turn the whole place upside down. But that was naïve, always was.”

Even if the prospective nightmare of Trump disrupting or ignoring the election goes away, the “loaded weapon” that Justice Jackson warned about will still be to hand. The enemies briefcase will still hold its list. Who knows whose names will be on it?